Building Trust by Design: DPDP Readiness for India’s Digital Future

A Shift in the Digital Landscape

Every time we book a ticket, fill out a government form, or access a public service online, we share something personal about ourselves – our name, phone number, Aadhaar, sometimes even our food preferences, medical or financial records. The same is also true for our fellow travellers or family members. For a long time, this data exchange happened quietly, without much public scrutiny. But the world was waking up to the risks and responsibilities of the digital age.

But as digital footprints grew, so did the concerns. Governments and citizens around the world began asking a simple question: who controls this data, and how is it being used? That question set off a wave of legal and policy responses. The United States passed the Privacy Act in 1974, followed by sectoral laws for health and finance. In Europe, Sweden and Germany pioneered national data protection laws in the 1970s, culminating in the EU’s Data Protection Directive of 1995, and later the GDPR of 2018- the world’s first comprehensive, enforceable, and globally influential privacy law.

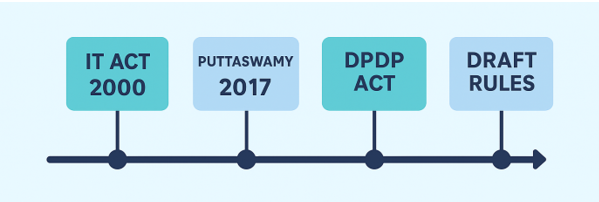

India, too, was watching these developments closely while shaping its own path. The Information Technology Act, 2000, provided the first framework for digital accountability, later strengthened by the IT (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011. The real turning point came in 2017 with the Supreme Court’s Puttaswamy judgment, which declared privacy a fundamental right. Soon after, the Srikrishna Committee Report laid the foundation for a dedicated law. Years of consultation, drafting, and deliberations culminated in the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023—India’s comprehensive response to the challenges of the digital era. Now, with the Draft DPDP Rules, 2025, the focus has shifted from principle to practice.

This blog isn’t just about what the law mandates. It’s about how government bodies, digital service providers, and developers can begin internalising these ideas, not merely for compliance, but to build platforms that citizens can genuinely trust. Especially those who are engaged in churning of such Data since decades.

What the DPDP Act Asks of You: Think CPRDG

If we had to capture the expectations of the DPDP Act in one simple acronym, it would be CPRDG standing for:

- Consent

Action: Obtain valid, informed, and unambiguous consent from citizens, present it in plain language, keep records, and allow easy withdrawal. - Purpose Limitation

Action: State the specific purpose before collection, process only for that purpose, set retention periods, and seek fresh consent if the purpose changes. - Rights of Data Principals (Citizens)

Action: Enable all rights with simple workflows and clear timelines. These include the right to be informed, right of access, right to correction, right to erasure when the purpose is over or consent is withdrawn, right to withdraw consent, right to grievance redressal, and right to nominate another person to exercise these rights where applicable. - Data Security

Action: Protect data at rest and in transit, restrict access on a need-to-know basis, maintain logs, test controls, and report breaches as required. - Grievance Redressal

Action: Provide an easy, responsive channel with a named contact, publish timelines, track resolutions, and learn from every complaint.

Let’s break each one down.

Consent is at the heart of the law.

According to the Oxford Dictionary, it means “permission for something to happen, especially given knowingly and voluntarily.”

The DPDP Act elaborates it as “any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the Data Principal’s wishes, by a clear affirmative action, signifying agreement to the processing of her personal data for the specified purpose.”

In simpler words: consent should not be assumed or hidden in fine print. If you are collecting personal data from a citizen, they need to clearly know what they’re agreeing to and why.

Purpose limitation builds on this. You can only use personal data for the reason you collected it. If the purpose changes, new consent is needed.

Rights of Data Principals (citizens) include the ability to access their data, correct it, or even request its deletion in certain cases. These rights must be respected and enabled with ease.

Data security is non-negotiable. When you collect personal data, you’re not just storing information, you’re holding on to trust. The law expects organisations to prevent breaches, restrict access, and ensure safe storage.

And finally, grievance redressal. Citizens should know whom to approach if something goes wrong. Every digital service handling personal data should have a dedicated mechanism for responding to complaints.

From Law to Action: What the Draft Rules Say

While the Act lays the foundation, the Draft Rules (2025) bring the framework to life. They detail how to:

- Design valid consent mechanisms

- Notify breaches within strict timelines

- Respond to citizen data requests

- Implement safeguards based on the nature and volume of data handled.

They also make space for different levels of compliance, depending on whether you’re a small department handling limited data or a large-scale data owner with nationwide reach.

Put simply, the draft rules get that one size won’t work for everyone. What they do expect is that every entity makes a genuine start and for now, we just wait for them to officially become the DPDP Rules.

A Simple Blueprint to Get Started

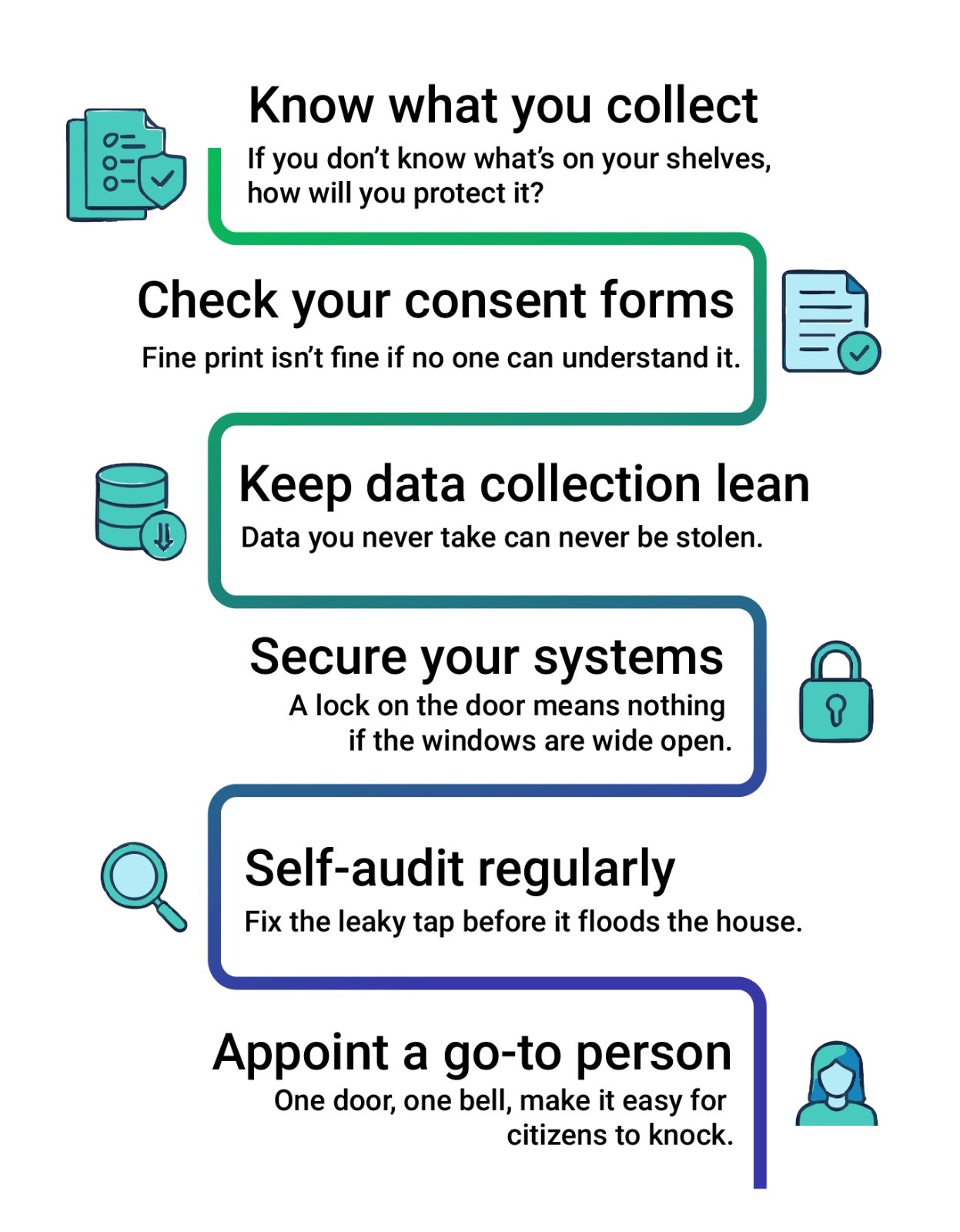

Think of this as your warm-up lap before the real compliance marathon. It doesn’t have to be complicated – here’s a simple 6-step blueprint any government office or digital service provider can start with.

Before you begin: list your purpose.

Write down exactly why you need each data point. If you cannot clearly justify a field, do not collect it.

- Know what you collect – If you don’t know what’s on your shelves, how will you protect it?

Do a quick internal review. What personal data are you collecting? Where is it stored? Who has access? - Check your consent forms – Fine print isn’t fine if no one can understand it.

Are they clear? Are they available in local languages? Can the citizen withdraw their consent later? If not, rewrite them. - Keep data collection lean – Data you never take can never be stolen.

Only ask for what you need. For instance, if a mobile number will do, don’t insist on Aadhaar or PAN. Collecting less reduces your compliance risk too. - Secure your systems – A lock on the door means nothing if the windows are wide open.

Data must be protected not only at rest but also in transit. Use access controls, encryption, and log all sensitive activity. The safer the system, the stronger the trust. - Self-audit regularly – Fix the leaky tap before it floods the house.

Don’t wait for a breach or complaint. Set up internal checks every few months. Document your actions, fix gaps, and keep improving. - Appoint a go-to person – One door, one bell, make it easy for citizens to knock.

Every platform should have a single point of contact for data-related queries or grievances. Citizens shouldn’t have to struggle to be heard.

NIC’s Role: Enabling a Privacy-First Digital India

As the key technology enabler of the Indian government, NIC is not just preparing itself for DPDP compliance, it is also enabling others to do the same. A comprehensive DPDP Compliance Framework is being developed to support departments and digital teams. It includes ready-to-use consent templates, risk checklists, model grievance workflows, and more.

This isn’t about ticking boxes. It’s about building systems where personal data protection is not an afterthought, but a design principle.

Data is also a Responsibility, Not Just an Asset

The personal data of citizens must not just be collected responsibly; it must be nurtured with care. It must be allowed to travel long and safe, across platforms, departments, and time. Every record we hold represents a citizen who placed their trust in a digital system. Our job is to honour that trust.

As we step into this new chapter of India’s digital journey, let’s not see compliance as a burden. Let’s see it as a chance to build credibility, to become better listeners, better designers, and above all, better custodians of data.

Because in the end, data protection isn’t just a policy. It’s a promise.